Working class Jewish people have played an important role in U.S. labor history, and in Communist Party history, with women workers — as in all working class communities — taking on leading roles.

During the early 20th century, Jewish immigrants were arriving in the United States, fleeing the repressive and anti-Semitic regimes of Europe. Many found work in the factories and sweatshops that dominated the urban landscape, where they endured grueling hours and brutal working conditions.

Many of the new arrivals had experience in tailoring and joined the booming textile industry in New York City. Alongside their garment skills, many brought with them a history of political activism in socialist organizations, such as the Jewish Labor Bund and Communist movements in their countries of origin.

Women workers in the garment industry faced particularly harsh conditions. They were systematically excluded from higher-level positions and often trapped in a subcontracting system that kept them underpaid and undervalued. These women typically earned less than half the wages of their male counterparts, even though the latter were labeled “semi-skilled” workers.

Tensions came to a head in November 1909, when the International Ladies’ Garment Workers’ Union (ILGWU) organized a mass meeting at Cooper Union Hall to discuss a general strike.

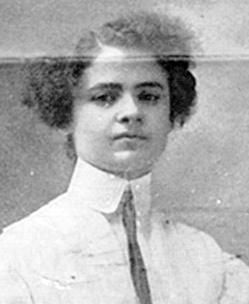

Among those in attendance was Clara Lemlich, a 23-year-old Jewish immigrant from the Russian Empire. The meeting was dominated by men who mostly called for caution. Lemlich, already on strike and recovering from a violent attack by hired thugs, demanded to speak. Taking the podium, she declared in Yiddish: “I have no further patience for talk … I move we go on a general strike!” The hall erupted in applause. Lemlich then took an oath before the crowd, swearing that if she broke her pledge to strike, her right arm should wither, referencing the biblical Book of Psalms: “If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, may my right hand wither.” For the Jewish worker’s movement of the time, the working class represented their “Jerusalem,” the sacred cause that must never be forgotten.

Among those in attendance was Clara Lemlich, a 23-year-old Jewish immigrant from the Russian Empire. The meeting was dominated by men who mostly called for caution. Lemlich, already on strike and recovering from a violent attack by hired thugs, demanded to speak. Taking the podium, she declared in Yiddish: “I have no further patience for talk … I move we go on a general strike!” The hall erupted in applause. Lemlich then took an oath before the crowd, swearing that if she broke her pledge to strike, her right arm should wither, referencing the biblical Book of Psalms: “If I forget thee, O Jerusalem, may my right hand wither.” For the Jewish worker’s movement of the time, the working class represented their “Jerusalem,” the sacred cause that must never be forgotten.

Within 24 hours of Clara’s oath, on November 24, nearly 20,000 garment workers went on strike. It is estimated that 75–80% of the strikers were Jewish women, immigrants between the ages of 16 and 25. The strike, known as the “Uprising of the 20,000,” demanded a 20% wage increase, a 52-hour workweek, overtime pay, and safer working conditions. Factory owners responded by hiring thugs to intimidate and attack the strikers. The police sided with the employers.

The strike gained widespread sympathy and support from other women’s organizations and continued until February 1910. While not all demands were met, significant gains were achieved, including fair pay for union members. Jewish women continued to organize and fight for workers’ rights in the following years and decades.

The Uprising of the 20,000 laid the groundwork for many more and increasingly more significant strikes, culminating in the “Great Revolt” later that year. Building on lessons learned during earlier strikes, the ILGWU coordinated a massive strike of over 50,000 shirtwaist workers. The strikers demanded a 48-hour work week, union recognition, double pay for overtime, and a closed shop system in which all workers must be union members.

As in previous strikes, hired thugs and police rained repression and violence on the workers, but the workers did not yield. By October, renowned attorney Louis Brandeis mediated a settlement, leading to the “Protocols of Peace” agreement between the union and factory owners.

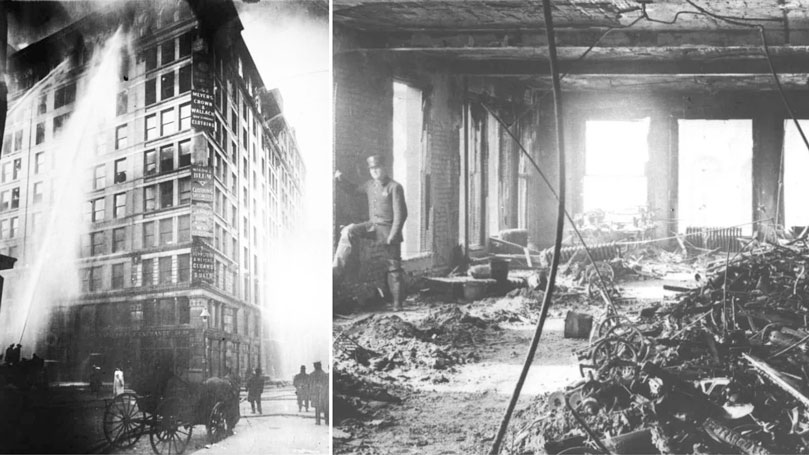

However, the struggle was far from over. In March 1911, New York City witnessed the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire — one of the worst industrial disasters in history. Workers were trapped inside when a fire broke out at the garment factory because management had locked the doors to prevent the workers from taking breaks. One hundred and forty-six people died, including 123 women.

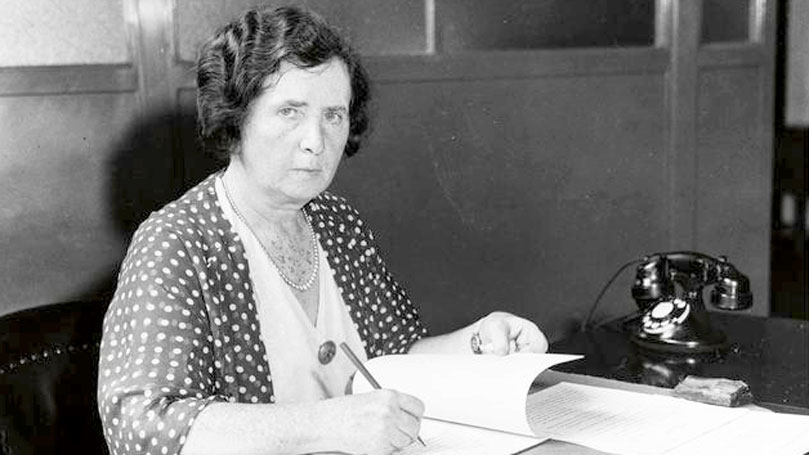

At the memorial to the victims, Rose Schneiderman, a prominent Jewish socialist, rose to speak:

“I would be a traitor to these poor burned bodies if I came here to talk good fellowship. We have tried you good people of the public and we have found you wanting … This is not the first time girls have been burned alive in the city. Every week I must learn of the untimely death of one of my sister workers. Every year thousands of us are maimed. The life of men and women is so cheap, and property is so sacred …

“I would be a traitor to these poor burned bodies if I came here to talk good fellowship. We have tried you good people of the public and we have found you wanting … This is not the first time girls have been burned alive in the city. Every week I must learn of the untimely death of one of my sister workers. Every year thousands of us are maimed. The life of men and women is so cheap, and property is so sacred …

“We have tried you, citizens; we are trying you now, and you have a couple of dollars for the sorrowing mothers and daughters and sisters by way of a charity gift. But every time the workers come out in the only way they know to protest against conditions that are unbearable, the strong hand of the law is allowed to press down heavily upon us.

“The strong hand of the law beats us back when we rise into the conditions that make life bearable. I can’t talk fellowship to you who are gathered here. Too much blood has been spilled. I know from my experience it is up to the working people to save themselves. The only way they can save themselves is by a strong working-class movement.”

Clara Lemlich would go on to join the newly formed Communist Party USA in the 1920s. During the Great Depression, she helped organize Housewives’ Councils, mobilizing women engaged in unpaid domestic labor. A lifelong member of the CPUSA, Lemlich was targeted during the McCarthy era and had her passport revoked in 1951.

Even in her later years, at 81, after moving into the Jewish Home for the Aged, she continued her activism by persuading management to join the United Farm Workers boycott of certain products.

Today, the Labor Arts Project gives the Clara Lemlich Award, honoring women who dedicate their lives to the struggle for justice and collective well-being.

In the years that followed, Rose Schneiderman led many workers’ movements and strikes. Through her prominent social activism she came to befriend Elenor Roosevelt and was appointed to the newly created National Labor Advisory Board in 1933, where she fought to include domestic workers in the newly created Social Security system and continued to advocate for wage parity for women workers.

While Lemlich and Schneiderman were among the more famous Jewish women labor leaders of their time, there were many others.

Fannia Cohn, another Jewish immigrant from the Russian Empire, became a key labor organizer within the ILGWU. In 1918, she was elected to lead the ILGWU’s educational committee, later becoming the union’s vice president. She was one of the great labor educators of her time. In 1921, she helped found the Workers’ Education Bureau of America; in 1924 she co-founded Brookwood Labor College.

Another example was Pauline Newman, who began working in garment factories at age 11 after immigrating from Russia. She became the first woman organizer hired by the ILGWU and worked alongside Lemlich during the Uprising of the 20,000. After the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire, Newman accepted a spot on the newly created Factory Investigation Commission, where she worked tirelessly for workers’ safety.

These are just a few examples of the countless Jewish immigrant women who devoted their lives to the fight for workers’ rights and social justice. To this day our party has many Jewish women within its leadership who continue to be in the forefront of fighting for social change.

Zionists and their allies have worked tirelessly for decades to erase the long and proud history of Jewish labor leaders, progressives, and communists. It is imperative not only to preserve this history, but to actively revisit and learn from it as we continue to build the modern socialist movement and confront both fascism and Zionism.

This Women’s History Month, the Jewish Committee of the Communist Party USA calls on everyone to remember this powerful history and honor the foremothers who laid the foundation for our movement. We further call on everyone to help preserve this history against the fascists and Zionists who wish to rewrite Jewish history to fit their reactionary ends.

Images: Clara Lemlich in a Shirtwaist, circa 1910 Rose Schneiderman (Kheel Center, public domain) / Rose Schneiderman (UAW Facebook page) / Fannia Cohn waves from an ILGWU Special Convention Train by Kheel Center (CC BY 2.0) / Pauline Newman (via nyclgbtsites.org, source unknown); Women garment workers (Triangle Fire Remembered, FolkWorks via Portside.org); Clara Lemlich (ephemeralnewyork); Garment workers on strike (AFGE); Triangle Shirtwaist Factory burning (jimcdn.com) / interior of the factory following the fire (jweekly.com); Rose Schneiderman (jimcdn.com); A child holding a sign in support of the United Farm Workers’ boycott (newsettlement.org); Rose Schneiderman in 1933 (Museum of the City of New York via nyclgbtsites.org); Fannia M. Cohn seated portrait at desk in garden (NYPL) / Pauline Newman (ilgwu.ilr.cornell.edu); Jewish Voice for Peace activists protest Wall Streets profiting from arms sent to Israel. (Screenshot of Jewish Voice for Peace / Rafael Shimunov video aired on Democracy Now)

Join Now

Join Now