The murder of George Floyd at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic and the ensuing global rebellion brought to the fore the advanced demands of the Black freedom movement in the ongoing struggle for freedom, democracy, and equality.

The abolitionist demands to “defund the police,” that is, to divest from police departments (up to and including complete defunding) and to invest in community care and programs like quality public education, social workers, jobs for all, conflict mediation, neighborhood response teams, and other forms of empowerment in oppressed communities have entered the mainstream debate between corporate politicians and justice advocates.

These demands have also led to a debate among progressive and left forces. Organizations like the National Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression (NAARPR) and the Movement for Black Lives (M4BL) have argued for community control over how our communities are policed. In this article, we offer the CPUSA’s viewpoint on community control of the police and related issues to contribute to the discussion.

The history of U.S. policing

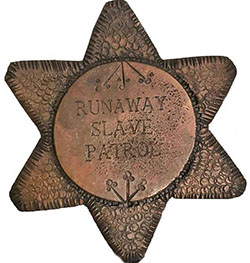

Policing and carceral measures have targeted racially and nationally oppressed peoples since the United States’ founding. From the settler-colonial genocide of the Native population to the kidnapping of Africans to be used as chattel slaves, U.S. capitalism was founded on white supremacy. The ruling class created slave patrols and overseers to break rebellions and stop slaves from escaping North. Slave catching became federal law in 1850, when the pro-slavery U.S. Congress updated the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793, wherein policing to maintain the slave system became a national priority, and U.S. marshals became slave catchers.

In the 19th century, as the U.S. sought to force its way into more Native territory, white colonists established local police forces to function as a colonial force. The Texas Rangers serve as one example. The Rangers were illegally created to protect white settlers in this Mexican territory, violating Mexico’s sovereignty. After the breakaway republic became a U.S. territory, the Rangers targeted Native peoples in what historians have termed “nothing short of an extermination campaign,” and they hunted down enslaved people as well.

In the 19th century, as the U.S. sought to force its way into more Native territory, white colonists established local police forces to function as a colonial force. The Texas Rangers serve as one example. The Rangers were illegally created to protect white settlers in this Mexican territory, violating Mexico’s sovereignty. After the breakaway republic became a U.S. territory, the Rangers targeted Native peoples in what historians have termed “nothing short of an extermination campaign,” and they hunted down enslaved people as well.

During the development of policing in the 19th century, factory owners also turned to the federal government to provide them with armed forces to break strikes and intimidate workers. Local and state governments soon followed suit. This “professionalization” enabled policing to be maintained for the powerful and wealthy.

After the overthrow of slavery in 1865, the slave policing system was abolished by means of what W. E. B. Du Bois called “abolition democracy,” or the elimination of the power of the slave-owning class power in favor of the newly free people.

Many Reconstruction governments enacted new policing systems that included sheriffs, marshals, national guards, etc., all of which were democratically controlled by the freed people and poor white farmers from the communities they lived in. This form of policing was used to quell counter-revolutionary forces like the Ku Klux Klan and other pro-slavery vigilantes and to defend the democratic gains of Reconstruction. Then came the betrayal of Reconstruction in 1877, when federal troops were removed from the South, and Congress provided reparations for the former slave-owning class to take back the land and political power.

White capitalists quickly enacted Jim Crow apartheid throughout the South through forced segregation, poll taxes, literacy tests, and other measures collectively known as the Black Codes. African Americans, now dispossessed of their promised land, became tenant farmers and sharecroppers for their former owners. “Criminality” was now used to re-impose slave-like conditions on the Black population by means of provisions in the 13th Amendment that allowed slave labor for prisoners.

The former slave patrols transformed into KKK-style night riders: terrorizing, murdering, and plundering Black lives and property. False accusations of sexual abuse and rape were targeted at Black men while other forms of super-exploitation of Black workers and tenants were employed to maintain white supremacy. Black people were imprisoned and forced into debt peonage to landlords and corporations for petty crimes, a system of convict leasing that lasted from the late 19th century until well into the 20th century; it was formally abolished in 1941. White supremacist rulers created policing and incarceration to maintain the Jim Crow system and capitalist profits.

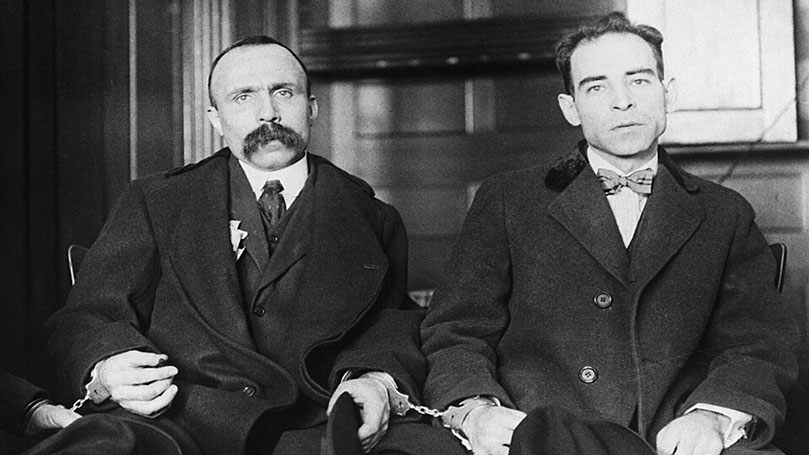

During the early to mid-20th century, the U.S. government and ruling class began policing people for their political beliefs. The imprisonment of socialist leader Eugene V. Debs for speaking out against World War I and later the Palmer Raids of 1919 led to the deportations, imprisonment, and death sentences of Communists, Socialists, Wobblies, Anarchists, and other radical forces, including Sacco and Vanzetti, who were executed in 1927. A second Red Scare during the 1950s targeted the Communist Party USA and others, leading to job loss, harassment, and imprisonment. During this same period, the Black freedom movement defeated the “separate but equal” doctrine, though deep patterns of segregation persisted in housing, jobs, and education.

The 1960s gave birth to a major upswing in the Civil Rights movement, resulting in a Second Reconstruction with passage of the Voting Rights and Fair Housing Acts along with a short-lived War on Poverty, but police repression continued apace. State-inspired domestic violence also increased, including assassinations and harassment from the FBI’s infamous COINTELPRO program. National Guard units were deployed to put down African American uprisings across the country.

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, notwithstanding the “War on Drugs,” a massive influx of narcotics into Black and Brown communities occurred, marking the beginning of the crack cocaine epidemic. This “war” was a key component of imperialist, anti-Communist reaction in Latin America, as arms were given to “contras” (militias fighting left governments and movements in Nicaragua and other countries) in exchange for cocaine that was then brought into the U.S. by the CIA.

With a reactionary drug policy being implemented by the U.S. government, militarized policing, “professionalization” of the police, and mass incarceration became commonplace. By the early 1990s, every state in the country had created a “mandatory minimum sentencing” law. The election of an extreme-right GOP majority in the House of Representatives under the banner of Newt Gingrich’s “Contract With America” hastened this process.

In 1994, the passage of the Crime Bill, spearheaded by Democratic Party President Bill Clinton, worsened the trend. The law, according to the ACLU, “encouraged even more punitive laws and harsher practices on the ground, including by prosecutors and police, to lock up more people and for longer periods of time.” The forces pushing for passage of the law drew on and exploited racist rhetoric about “super-predators,” gang-bangers, and drugs to specifically target Black and Brown communities.

Today the U.S. hosts the largest prison population on the planet, disproportionately incarcerating African Americans and Latinos. A prison industrial complex extends from coast to coast, composed of both state-run and private prisons, where many prisoners are serving long sentences for drug-related offenses.

Today the U.S. hosts the largest prison population on the planet, disproportionately incarcerating African Americans and Latinos. A prison industrial complex extends from coast to coast, composed of both state-run and private prisons, where many prisoners are serving long sentences for drug-related offenses.

Due to ongoing high unemployment rates, particularly among African American and Latino youth, a school-to-prison pipeline serves this complex, which employs inmates fighting fires, in call centers, and other occupations at literal pennies on the dollar.

In many cities police employ “Broken Window” policies and similar draconian tactics to round up and shake down youth of color, in order to feed the prison and related industries. In others, young Black women and men are regular victims of police killings. In fact, the number of police shootings has increased rather than decreased, despite the huge public outcry after the murders of Breonna Taylor and George Floyd. It is in these circumstances that the demand for community control of the police has arisen.

Our demand: Community control of the police

“Community control,” that is, the ability of Black folk to have control over every aspect of their lives, has been a central demand of the African American freedom movement as early as the Reconstruction period. One form it took back then was the fight for the promised but never delivered 40 acres and a mule. Another was access to public education, one of the longest-lasting radical reforms born during Reconstruction. Still another was the right to vote and run for political office..

From the fight for control over land in the late 19th century to the 1940s struggles in Harlem led by CPUSA members Maude White Katz and Doxey Wilkerson for control over schools, to today’s demand for elected bodies that would control police activity, budgets, and practices, the fight for community control is a fundamental part of the battle for democracy – including radical reform of the very institutions of state power.

Advanced demands in the 1960s in response to police occupation forces in poor Black “ghettos” and working-class communities led Black Panther Party (BPP) leaders such as Bobby Seale and Fred Hampton to push for control over police forces, which then and now are dominated by white supremacists and former Ku Kluxers devoted to the maintenance of a white-dominated, capitalist society.

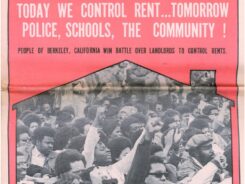

In 1969, after spending many years developing a self-defense program for the BPP which included a community cop watch, the Oakland chapter of the BPP was able to organize and place a “Community Control of Police” referendum on the ballot in Berkeley, California. This referendum called for real investigative powers through community review boards to recommend action against police officers for misconduct and a body of police commissioners duly elected by the people of the community. The referendum lost by only one percentage point. As Bobby Seale put it, “The concept of greater control by the people and the community of their police department is a constitutional democratic necessity.”

In 1969, after spending many years developing a self-defense program for the BPP which included a community cop watch, the Oakland chapter of the BPP was able to organize and place a “Community Control of Police” referendum on the ballot in Berkeley, California. This referendum called for real investigative powers through community review boards to recommend action against police officers for misconduct and a body of police commissioners duly elected by the people of the community. The referendum lost by only one percentage point. As Bobby Seale put it, “The concept of greater control by the people and the community of their police department is a constitutional democratic necessity.”

Seale argued:

Their [the police] real power is manifested in the organized guns and force. But we’re saying that the people in this community, the people in this country, don’t have any control over that organized guns, force, and power. We’re saying that the capitalist, the racist, and others have control over it. And we’re saying that we want to change it, that we want to revolutionize it, turn it over into the hands of the people, for a new process to occur. We’re saying we want community control. (Chicago Community Control of the Police Conference, June 1, 1973)

Today, the National Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression (NAARPR) is continuing this work.

The NAARPR, founded in 1973 out of the struggles to free both Angela Davis and Joanne Little, was recently re-established as a national organization with community control of police as its central demand and contribution to the Black liberation movement and the struggle for full equal democratic rights. Community control of police is a primary demand that centers the African American people’s movement as an independent force fighting for equal democratic rights and governance. The demand also has application to all working-class communities: Latino, Asian, Middle Eastern, Native American, and white. Indeed, the realization of community control is in the interest of the working class as a whole.

To dismantle and end the racist prison industrial complex as well as the carceral systems that enable it (which includes the police), institutions such as all-elected civilian control boards could hold real investigative and policy-making powers in their cities and communities, and have full authority over hiring and firing and the local city police budget. Community control is meant to shift the balance of power and give oppressed communities complete democratic control over public safety and hold murderous police officers accountable.

Civilian review boards, which were enacted as a reformist reaction to the BPP’s campaigns for community control in the 1970s, are not community control. They have very little authority and few resources to enact any change. Most were designed to provide a safety valve for community anger to blow off steam at police violence. They were intended more to improve community-police relations than to punish and root out police misconduct. Over 200 cities have them in some form, none of which have the objectives of the original proposals.

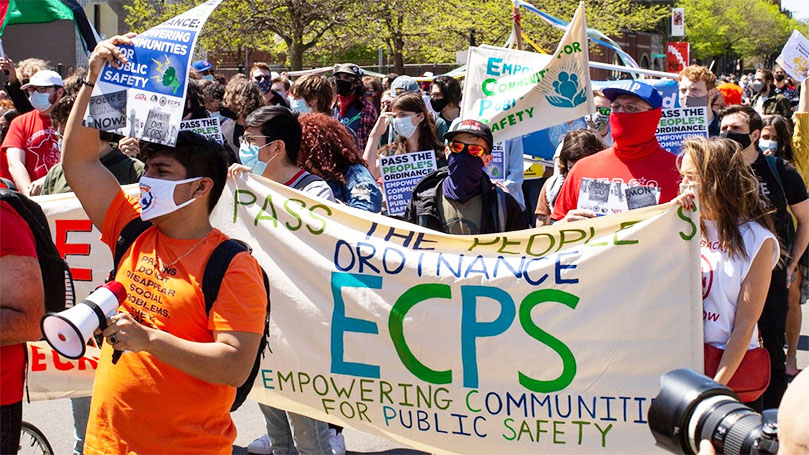

But things are changing. For example, a recent victory for real community control happened in Chicago in July 2021. The Empowering Communities for Public Safety (ECPS) was passed by the Chicago City Council with a majority of alderperson and community support. This ordinance creates a community commission for public safety and accountability and local district councils that will have power over the police accountability system in Chicago.

As a founding organization of the NAARPR in the 1970s and current coalition partner, the Communist Party USA views the demand for community control of police as central in the struggle for Black lives to tilt the balance of forces toward democratic movements and to stop the killing of racially and nationally oppressed people in the United States by the police.

In its very essence, it is a demand for power both to and from the people, in other words, to radically reconfigure the very functioning of government at the city, neighborhood, and community level. Why? Because policing is by definition a function of the capitalist state, whose main purpose is to protect property by means of repressing working-class communities. Community control demands that this formula be fundamentally altered. Now the very functioning of policing would be redefined. Instead of protecting big capital and private property, empowering the people would be the main purpose of these institutions.

We demand the implementation of directly elected civilian control boards that have the full and unconditional power to determine:

Final authority over police policy, oversight policy, and budget, including writing and reviewing;

Full authority on disciplinary measures and legal recourse, including subpoena power and the convening of grand juries;

Hiring and firing power over the police chief or superintendent, all officers on the force, the head of any existing oversight or review boards and offices, and its members;

Full access to all investigations by the oversight or review institutions;

Broaden the scope of investigations to include all allegations of misconduct, including sexual assault;

Negotiation of police union contracts;

Exclude all current and former law enforcement agents from serving on the board.

Conclusion

The fight for community control is part and parcel of the many-sided fight for democracy and working-class power. It is one dimension of that fight. With respect to the government, there are other dimensions, for example, control of school boards, city councils, zoning commissions, and county commissions. Policing, because of its immediate daily presence in nearly all aspects of a community’s life, is key.

African Americans, Latinos, Asians, Middle Eastern peoples, and Native Americans have been systematically denied access to, let alone equal control over, these institutions. Indeed, their historic oppression has rested on this denial, creating systems of inequality that ripple throughout all aspects of economic, social, and political life. These systems must be dismantled.

The position of the Communist Party of the United States on the question of racially and nationally oppressed people is that they are entitled to immediate and unconditional political, social, and economic equality. From the fight for voting rights and the fight for full representation in political office to the fight against mass incarceration and police terrorism, people of color are struggling for freedom from oppression in this country.

In its political essence, the freedom struggle of African Americans is a struggle to gain adequate political and economic power to secure and safeguard their rights as citizens and as a component nationality, a historically oppressed national minority in the evolving multi-national United States. This is a political struggle that is consonant with the effort of the working class and the totality of anti-monopoly progressive forces for genuine representative government, for real democracy. It is at once a democratic struggle and a class struggle.

It is a democratic struggle in that Black people fight to eliminate all disenfranchisement laws and ruses. African Americans demand real political power in the areas of their majority to provide for maximum representation everywhere and at all levels of government.

It is a class struggle in that the overwhelming majority of African Americans are workers suffering from unequal wages, housing, health care, and access to education – in other words, every aspect of economic and social life. The racial wage gap (a source of super-profits), for example, since the dawn of the new century, instead of lessening, has actually grown.

The struggle for African American liberation takes place in a period of a sharply deepening crisis of U.S. capitalism in the advanced stage of the general crisis of world capitalism. African Americans take pride in and experience deep inspiration from the historic achievements of working peoples around the world. The dictum of Frederick Douglass that “a blow struck for freedom anywhere, is a blow against tyranny everywhere” is a part of their national traditional mindset.

The fate of people of color in this country is deeply connected to the fate of the peoples of our planet. It should not be forgotten, for example, that African Americans and Latinos were the prime targets of the mortgage companies and banks that precipitated the sub-prime crisis and the Great Recession. In this racist drive for super-profits, the banks almost brought down the world economy and caused the largest wealth loss in Black and Latino history.

Likewise, the U.S. imperialist exploitation of Africa, Asia, and Latin America is connected to

and has its home equivalent of the new Jim Crow assault on African Americans through mass incarceration, the GOP’s attacks on critical race theory in schools, and continued police terrorism and murder. The grotesque face of racism is outfitted with new cosmetic masks of deception and misrepresentation. The very concept of “equality” is abused and misused to continue racist practices of robbing people of color of their just economic and civil rights.

The struggle for equality and real democracy is at its basis a struggle for the transfer of power from the hands of the state monopoly ruling class to the control of the people. That is what community control of the police is all about.

These struggles cannot be received as a gift from the hands of the very monopolists who fashioned the undemocratic system in the first place, and concessions that can be wrested from them through struggle, while important, will never measure up to either need or justice. But the demands must be made, and it is the people who must wrest in from the one percent that controls it now.

By uniting with our natural allies in labor, women’s organizations, LGBTQ movements, and youth in the demand for community control, an important step can be taken on the road to a government of people’s power and working-class leadership. This is what it’s all about.

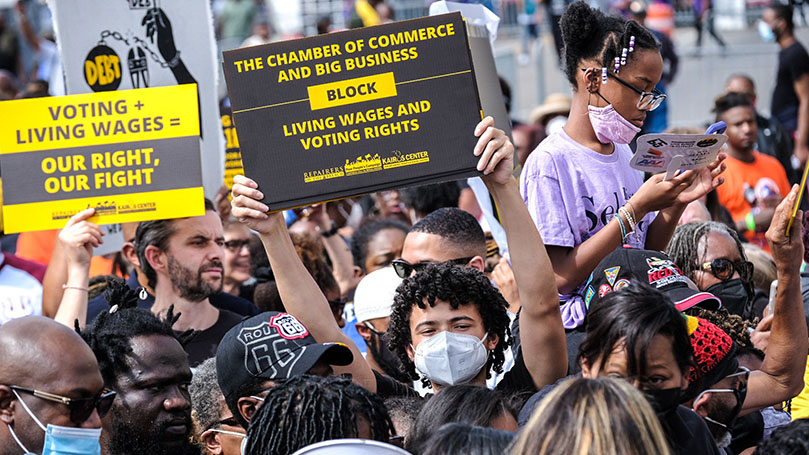

Images: Chicago march for ESPS, CAARPR (website); Slave patrol badge, Liveauctioneers.com; Sacco and Vanzetti, Wikipedia (public domain); March to end racial profiling, longislandwins, Flikr (CC BY 2.0); Cover of Black Panthers Party newspaper, tracy rosenthal (Twitter); CAARPR rally, Scott Marshall, People’s World; Pro-ESPS sign, CAARPR (website); Poor People’s Campaign rally, Steve Pavey, Kairos Center & Poor People’s Campaign, PPC Facebook.

Join Now

Join Now