The Biden administration has been described as potentially transformative, equaling Lyndon Johnson’s years and possibly even rivaling Franklin Roosevelt’s tenure. While it’s still early, such comparisons may not be far off, considering the possible impact of pending environmental, infrastructure, voting, and labor rights legislation. If made into law (and at this stage that’s still a big if, thanks to Mr. Manchin & Co.), these bills would go a long way to not only rescue the country from the scourges of the health, environment, racial, economic, and political crises that currently beset it, but also mark a break with the neoliberal doctrine that has gripped decision making since the 1980s. Or would it?

This question is brought into bold relief when considering the nine-month-old administration’s “inflection point” foreign policy doctrine. It too might be transformative, but the comparison now would not so much be to LBJ and FDR but rather to Harry Truman, Jimmy Carter, Dwight Eisenhower, and even Richard Nixon. Transformation, in this instance, would represent a 180-degree turn towards positions not assumed since the height of the Cold War, away from not only the Obama administration’s rather constrained international posture, but from the very concept of peaceful coexistence that at least, in part, influenced U.S. foreign policy for the past half century.

How so?

Having retreated from the Afghan theater in the war on terror, Mr. Biden’s administration now seems hell-bent on opening up a whole new battlefront, replacing “radical Islam” with China, socialism, and what are deemed autocratic states. In today’s Cold War redux, China is seen “as America’s existential competitor, Russia as a disrupter, Iran and North Korea as nuclear proliferators,” writes the New York Times.

Indeed, news of the military agreement between Australia, the U.S., and the U.K. aimed at China underscores this new direction.

“We’re in competition with China and other countries to win the 21st century,” the 46th president recently declared. “We’re at a great inflection point in history.” “On my watch” he later boasted to reporters, China will not achieve its goal “to become the leading country in the world, the wealthiest country in the world, and the most powerful country in the world.”

The administration’s lurch rightward in foreign affairs flies in the face of U.S.-China detente that dates from 1979 with Deng Xiaoping’s entry onto the world stage and China’s “opening up.”

Only two years ago, Biden was referring to China’s leadership as “nice people.” What changed?

Thomas Friedman in a recent Times column sums up the U.S. rationale succinctly, identifying technology theft, Hong Kong, the alleged mistreatment of national minorities, notably the Uygurs, and Xi Jinping’s leadership. The last factor tops Friedman’s list: “Then there is the leadership strategy of President Xi Jinping, which has been to extend the control of the Communist Party into every pore of Chinese society, culture and commerce.” He continues, “This has reversed a trajectory of gradually opening China to the world since 1979.”

Trade is another key issue. Here Friedman suggests that, to end the tariffs imposed by Trump, China must first end its commodity subsidies. “Many U.S. businesses are pushing now to get the Phase 1 Trump tariffs on China repealed — without asking China to repeal the subsidies that led to these tariffs in the first place. Bad idea.”

Clearly, what irks U.S. capital and its apologists are primarily two issues: the CPC’s campaign to deepen the role of the Communist Party and the country’s commodity export policy, in other words, how what’s called “socialism with Chinese characteristics” handles trade. The party has been campaigning against corruption and attempting to politically and ideologically reinforce itself, an effort that makes the likes of Friedman cringe. The op-ed writer’s call to “end subsidies” is basically a demand to dismantle China’s organization of production — in other words, its drive toward socialism. One might ask Mr. Friedman, should the U.S. end its subsidies to agriculture and oil as well?

Some might call these questions of national sovereignty where outsiders dare not intrude. Friedman, obviously, has other ideas as he quips: “When dealing with China, speak softly but always carry a big tariff (and an aircraft carrier).” Small wonder the Chinese general secretary replied in his speech celebrating the 100th anniversary of the CPC with such vigor to the “sanctimonious preaching” of those who have the gall to tell them what to do and combine it with threats of military force.

Biden’s views, it seems, are widely shared in the circles of the 1 percent. Indeed, a new bipartisan ruling-class consensus has taken shape. Jake Sullivan, the administration’s current national security advisor, argued in a Dartmouth College interview in 2019 that the national security establishment of both parties in recent years had come to the conclusion that “we totally screwed up, we got China all wrong” in assuming that the People’s Republic would become more “liberal” and “responsible stakeholders” as they became integrated into the “rules based order” (meaning the WTO and other international bodies).

When that didn’t happen, the powers that be concluded, says Sullivan, that the U.S./China equation is “no longer about cooperation; it’s about competition and competition in a way is kind of a code word for confrontation.”

Enter Cold War 2.0.

Yet this is a standoff of a different type. U.S. policy towards the USSR and the socialist community of nations was premised on the strategy of containment and the hope that these newly emerging societies would collapse under the weight of their own inertia. Today’s plans toward China instead posit a zero-sum, winner-take-all pursuit of U.S. imperialist objectives. Last spring Bernie Sanders sounded the alarm in Foreign Affairs: “It is distressing and dangerous, therefore, that a fast-growing consensus is emerging in Washington that views the U.S.-Chinese relationship as a zero-sum economic and military struggle.”

Kurt Campbell, a Biden loyalist who advised the vice president during the Obama years and is now a member of his National Security Council responsible for China, put it this way last spring at a Stanford conference: the period of “engagement [with Beijing] has come to an end.” U.S. policy is now under a “new set of strategic parameters,” says Campbell. Fierce competition, according to the NSC staffer, is the new framework for the relationship.

The war on terror helped fuel far-right extremism, leading to Trump’s Muslim ban and ultimately January 6th.

Needless to say, this language is a far cry from the diplomatic niceties accorded state-to-state relations in normal times, at least in public. Still it should be pointed out that these not-so-veiled threats must be weighed against Biden’s pledge to end the forever wars and repeated ill-fated U.S. attempts at nation building. At the same time, one might rightly ask, is the White House speaking out of both sides of its mouth? Democrats, after all, are notorious for moving to the right on foreign policy, an alarming trend in normal times but extremely troublesome in light of the ongoing fascist threat. After all, it’s no secret that the conduct of the war on terror helped fuel far-right extremism, leading to Trump’s Muslim ban and ultimately January 6th.

Here Democrats contend that it’s possible to confront on the one hand (e.g., pulling back on technology transfers) and cooperate on the other (climate change), a most dangerous game.

Not surprisingly, Republicans just love it. Steve Bannon, alt-right gadfly and former Trump strategist, has long painted China as an existential threat. Now it seems, at least in spirit, ruling elites have found common cause.

The casual equating of right and left “authoritarianism” obscures fundamental differences between social systems.

Upon hearing the news, Hal Brands of the right-wing American Enterprise Institute waxed ecstatic: “Biden views . . . competition as part of “a fundamental debate” between those who believe that “autocracy is the best way forward” and those who believe that “democracy will and must prevail,” a patently false juxtaposition if there ever was one. Here the casual equating of right and left “authoritarianism” obscures fundamental differences between social systems.

According to Brands, the U.S. is contemplating a three-pronged response: forging a new coalition with advanced capitalist nations, pursuing international responses to transnational crises like COVID, and reinvesting in infrastructure and technology in order to contest China and other rivals.

Untangling the two countries’ economic ties will be no easy task, given the existing level of integration. Another observer, a former editor of Foreign Policy, argues that some measures already underway are more aggressive than those pursued by Trump:

Since taking office, Biden’s administration has maintained former President Donald Trump’s trade sanctions against China. It has worked with the Senate to pass a massive, quarter-trillion-dollar industrial policy bill aimed at boosting U.S. competitiveness. It has launched a Buy American campaign that cuts foreign firms out of the extremely lucrative U.S. government procurement market. It has worked to block Chinese acquisitions and investments inside the United States and to keep Chinese students and researchers out of the country. And on June 17, Biden signed an executive order banning Americans from investing in Chinese companies linked to the military or to surveillance technology.

Additionally, “the U.S. is looking to impose further restrictions on the export of leading-edge semiconductor technology to China, and the White House has raised the possibility of an Indo-Pacific-wide digital trade deal that excludes Beijing.”

The situation is growing increasingly complicated. Consider that the foundations of the administration’s international objectives, spelled out in an Interim National Security Strategic Guidance, are premised on benefiting working- and middle-class families: “We have an enduring interest in expanding economic prosperity and opportunity,” the document’s authors aver, “but we must redefine America’s economic interests in terms of working families’ livelihoods, rather than corporate profits or aggregate national wealth.”

Make no mistake: this is new. Without a doubt, a redefinition of U.S. economic interests, prioritizing working-class well-being over corporate profits, would indeed be welcome. That it’s framed within the context of U.S. national security is also noteworthy. The couching, however, of these ideas within the framework of such retrograde language and plans is extremely problematic. Biden’s national security advisor, Mr. Sullivan, it appears, is among the chief authors and architects of this strategy.

What’s behind it? Sullivan himself seems to have been moved by the 2016 election campaign and the realization of “how profoundly such a large segment of our country felt their government wasn’t working for them.” Hence he concluded that “the strength of U.S. foreign policy and national security lies primarily in a thriving American middle class, whose prosperity is endangered by the very transnational threats the Trump administration has sought to downplay or ignore.”

Bernie Sanders’ campaign too had an impact: “I didn’t always agree with his ultimate policy solutions, but there’s no question he connected with how much of America experiences and perceives the impacts of systemic inequality, and this sense that the system was somehow working against them.”

Hence Sullivan’s belief in the need to address transnational issues like the pandemic, global warming, and trade along with massive reinvestments in infrastructure both traditional and human. But these are one individual’s subjective considerations, hardly a basis for the class policy shift that’s in the works. What then could be among the objective factors?

Here a shift away, if not a break from, neoliberal policy may be part of a wider change in advanced capitalist countries. One writer points to the nationalization of a steel plant in the UK and writes that in “Europe, the EU is in the process of overhauling its State Aid rules to allow greater government support to industry, citing the need to meet competition from China.”

A big issue, it’s argued, is the growth of big data and the absence of rules governing intellectual property, both of which demonstrate the need for government intervention:

The broader point here is that the material base of the global economy has, in the past decade, been decisively reshaped around data technologies and a major new competitor economy outside the West, and that this in turn has promoted a direct challenge to neoliberal norms of government across the globe. To the extent that the pandemic has accelerated the shift toward the digital economy, and has expanded the range of government intervention, it has brought neoliberalism’s death rather closer.

Then there are the objective imperatives of real life. Confronted with the aftermath of January 6th and the events leading up to it, the objective of the Biden Administration, at first glance, seems to be to rewrite the social contract in fundamental ways by addressing working-class concerns with the added benefit of winning back some of those influenced by Trump: “Biden has been pursuing investments in scientific research and development, digital and physical infrastructure, and other areas to improve competitiveness and address working- and middle-class alienation,” offers a Bloomberg analyst. He continues: “In Biden’s view, improving the economic fortunes of the middle class is insurance against a Trumpist resurrection and a way of strengthening the domestic foundations of U.S. diplomacy.”

Other commentators appear either skeptical or at best nonplussed: “Allies are also asking what Biden’s concept of a foreign policy for the middle class can do to advance prosperity in the free world as a whole. Some worry that it is just a softer version of Trump’s protectionism, skeptical of free-trade agreements and partial to tariffs.”

But clearly, there’s another goal at work here. Team Biden’s Security Guidance hints at it: “Anti-democratic forces use misinformation, disinformation, and weaponized corruption to exploit perceived weaknesses and sow division within and among free nations, erode existing international rules, and promote alternative models of authoritarian governance.”

Who, it must be asked, is advocating “alternative models” of governance? Thomas Wright, writing for the Atlantic, comes close to an answer. “In his [Biden’s] view, the United States is in a competition of governance systems with China.” It’s one thing to compete as to who is best, East or West, and quite another to frame such competition in far broader and more insidious terms.

Nader Mousavizadeh, founder and C.E.O. of Macro Advisory Partners and an advisor to the late Kofi Anan, quoted in the Friedman op-ed, hits the nail directly on the head. Questioning the advisability of the entire Biden foreign policy project, he asks, “Are we sure we understand the dynamics of an immense and changing society like China well enough to decide that its inevitable mission is the global spread of authoritarianism?”

Social revolution is not an exportable commodity — it cannot be shipped in and imposed from without.

It’s a damn good question. Biden and company have been led to believe that China’s main purpose in life is the global export of its revolution. But this is clearly a misreading of intentions. As a question of practice, “socialism with Chinese characteristics” is very China specific, a model based on that country’s unique conditions. As a matter of theory, as Gus Hall used to say, “socialism is not a foreign import.” In other words, there are no universal models of socialism fit for every time and place. If the 20th century has proven anything, social revolution is not an exportable commodity — it cannot be shipped in and imposed from without.

U.S. imperialism seems particularly alarmed at China’s Belt and Road initiative, a wide-reaching infrastructure initiative aimed at developing nations. So alarmed in fact, that in response to Belt and Road, the U.S. pushed the G7 in June to launch a lamely labeled Build Back Better World (B3W) program aimed at a similar international audience.

When it’s all said and done, the linking of a left progressive domestic program to anti-communist foreign policy aimed at “cancelling” China’s drive toward socialism marks a new stage in U.S. imperialism’s effort to regain lost positions and right the ship of state. As a tactic, however, the ploy is not new. During Cold War 1.0 sections of the left, particularly in the European social democratic movements, were encouraged to take similar positions. It would be a tragedy for history to repeat itself here at home.

The danger, of course, is that this left/right pairing of bread-and-butter priorities at home with great power imperatives abroad carries with it the potential for faux populist appeals with all the dangers that come with it. Instead of responding to the genuine aspirations of Black Lives Matters movements, immigrant rights, union strikes, organizing drives, and shop floor activism, in other words, the “socialist moment,” the nation could be diverted toward potentially nationalist and xenophobic paths – the dramatic increase in anti-Asian hate and violence is a case in point.

The Biden administration has already extended the Trump sanctions against Cuba and remains hostile to Venezuela. What country will be next? Nicaragua now appears to be in imperialism’s sights.

Setting this aside for the moment, another question looms large: are any of these actions in the objective interests of African American, Latino, Asian American, Native American, and white workers? And how will the labor movement respond? Hopefully not with a new round of China bashing in exchange for a few pieces of badly needed silver.

Notwithstanding these challenges, the concept of connecting security to working-class interests should not be dismissed out of hand. It would be a huge mistake to frame this problem narrowly. The issue is separating, if possible, these more-than-worthy domestic intentions from their entrapment in Cold War 2.0 designs.

The good news here is that some early on have seen through the Cold War rhetoric and are taking sharp issue with it. As pointed out above, already in late spring Bernie Sanders took exception to the emerging consensus and called for its reversal. Sanders, who also buys into a bit of China bashing, nevertheless correctly noted, “The primary conflict between democracy and authoritarianism, however, is taking place not between countries but within them—including in the United States,” and called for a global minimum wage to help address worldwide inequality. Biden has proposed a global minimum corporate tax, and the G20 and OECD have agreed in principle on a 15% minimum corporate tax. This is a good beginning if implemented. US corporations currently pay an effective corporate tax of 17%.

Importantly, around the same time, 40 organizations took issue with the hawkish U.S. policy toward China, warning that it threatened climate collapse. Politico writes, “It’s the latest salvo in the months-long drama between progressive Democrats who say cooperation on climate change should take precedence over competition with China, and moderates who think the administration can do both things at once.”

The article continues:

The progressive organizations, including the Sunrise Movement and the Union of Concerned Scientists, “call on the Biden administration and all members of Congress to eschew the dominant antagonistic approach to U.S.-China relations and instead prioritize multilateralism, diplomacy, and cooperation with China to address the existential threat that is the climate crisis,” their letter reads. “Nothing less than the future of our planet depends on ending the new Cold War between the United States and China.”

It seems that the Biden administration itself is not of one mind on these issues. The Atlantic writes that “some in the party’s foreign-policy establishment hope that his views on China are not yet settled, and that he will moderate his rhetoric and outlook over time, deemphasizing the contest between democracy and authoritarianism. They worry that the United States could find itself embroiled in an ideological struggle with China akin to the Cold War.”

The divisions extend deep into the administration: “A Biden-administration official [said] that, while the top foreign-policy officials are simpatico with the president, some in the government share the restorationists’ concerns, while others have yet to grasp the significance of the president’s statements.”

The Biden administration is also risking a hot war with Russia over the Ukraine and with Iran in the Middle East. US imperialism is being challenged at the same time that Biden attempts displays of resoluteness in showing US military and diplomatic “strength.”

Thus, there is plenty of room and opportunities to push the administration in a better direction, and pushing is a must. The goal here must not necessarily be to change the administration’s hearts and minds, but compel change with real mass on-the- ground politics. This should include a change of personnel in the State Department, which, having already badly managed the withdrawal from Afghanistan, is now pushing the country into a new balance of military and nuclear terror with China and possibly Russia. The future of human civilization may depend on what mass movements do. It’s either peaceful coexistence or no existence.

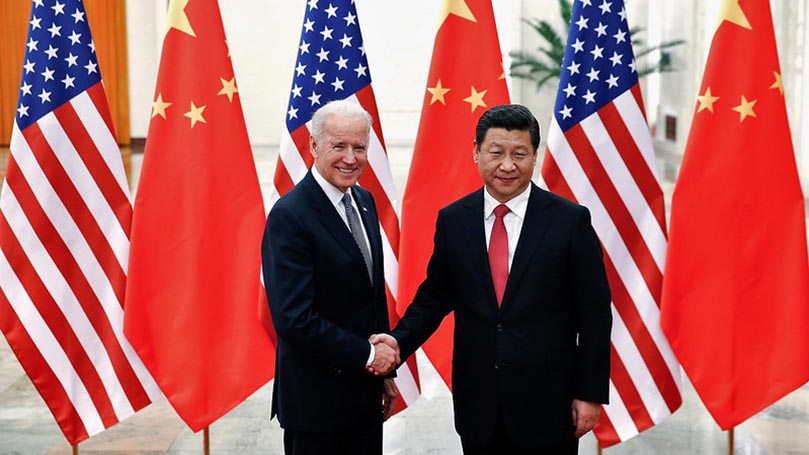

Images: top, USDA (CC, public domain); Biden and Xi, 李 季霖 (CC BY SA); Fascist threat, ep_jhu (CC BY-NC 2.0); Technology, Ugochukwu Ebu (Pixabay); Black Lives Matter, Anthony Quintano (CC BY-NC-SA ).

Join Now

Join Now