In the arduous profession of the revolutionary, death is a frequent occurrence.

— Che Guevara

It is the most reproduced photo and “the most famous photograph of the 20th century” (Anatomy Films, p. 1). It apparently surpasses da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, Munch’s Scream, U.S. Marines raising the flag at Iwo Jima, and Marilyn Monroe with skirt billowing upward as “the most replicated image ever” (Anatomy Films, 1).

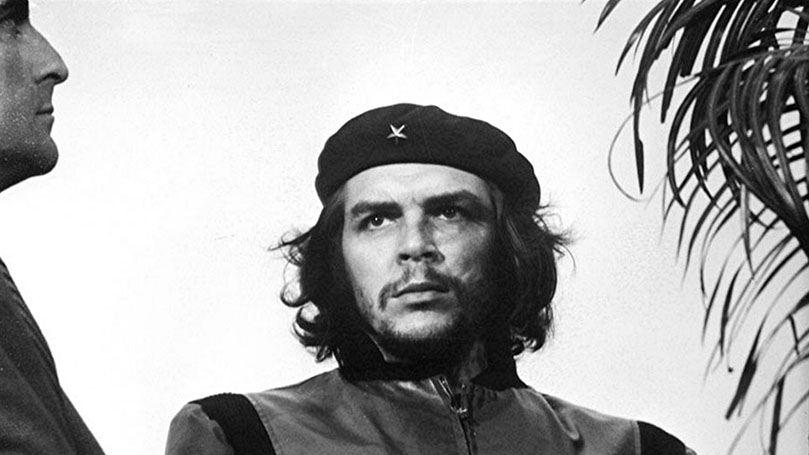

The photo is entitled Guerrillero Heroico. The subject is Che — Argentine slang for “hey” or “hey buddy” or “friend.” More properly, it is Commandante Ernesto “Che” Guevara de la Serna.

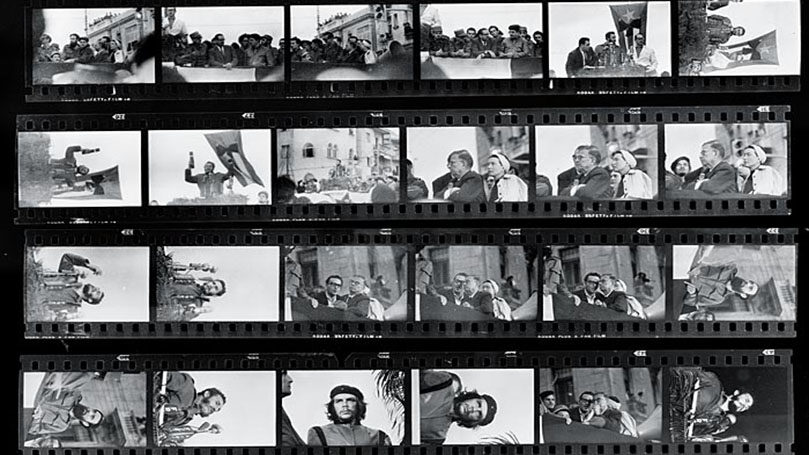

On a damp, cold day, March 5, 1960, Cuban communist and photographer Alberto Díaz Gutíerrez Korda snapped a photo with “an ageless quality, divorced from the specifics of time and place” (Casey, 312). The Cuban people and their leaders were gathered for a protest rally after a Belgian freighter carrying arms to Cuba was blown up by enemies of the revolution. Also present that day were Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir.

Che was notoriously camera shy, but “little did he know he was staring straight into the firing line of Korda’s trusty Leica camera” (Casey, 27). As “Che’s face jumped into the viewfinder, [t]he look in Che’s eyes startled Korda so much that he instinctively lurched backward and immediately pressed the button” (Anatomy Films, 4). Just as Korda instantly observed, his eyes are captivating: “pensive, determined, defiant, meditative, or implacable, his expression is — like the Mona Lisa’s smile — difficult to put a finger on” (Casey, 36). His eyes are “looking right through us, as if he is focused on some far-off horizon with its promise of a future utopia” (37).

The blast in the harbor had killed hundreds of Cubans and suppressed the joy of the recent revolution. Che had rushed to the scene: “No wonder Korda had described Che’s look as ‘angry and grieved’. It was the face of Ernesto Guevara mad as hell and eager to avenge bloodshed, yet also aware of the immense heartache associated with the struggle he’d chosen for his life (Casey, 38). By March 5, 1960, Che was already famous worldwide, but Korda’s photo brought beatification and immortality, giving “Che his afterlife” (347).

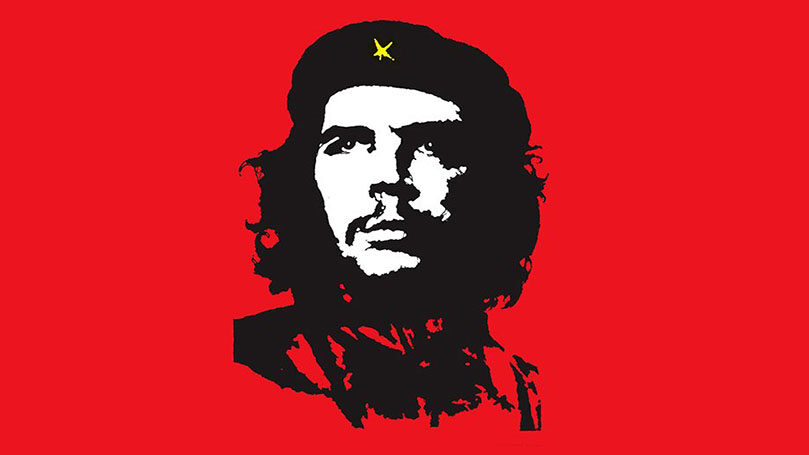

The shot certainly went global, but it’s not clear exactly how the “Korda Che made its transition into the world” (Casey, 71). The black-on-red image was prominently displayed in the streets and around the barricades of the 1968 Paris uprisings, although the source of the French Che posters was unknown (126). Marxist soldier/revolutionary Che had become Left Bank hippie Che, representing honesty and integrity and “the very thought of social transformation” (199). The “Korda Che” became “the universal symbol for the act of following one’s convictions” (262).

The Korda Che is also a reminder of how capitalism swallows everything and spits it out again, commodified, packaged, and marketed: “From its very beginnings down to the present, business dogged the counterculture with a fake counterculture, a commercial replica” (Casey, 130). The image is now everywhere, affixed to posters, coffee mugs, condoms, beer bottles (Che did not drink), pillow covers, T-shirts, and “even tattooed on the torso of Mike Tyson!” (Anatomy Films, 1). Yanqui capitalism has stripped the image of its historical and political roots, including Che’s Marxist ideology so that “the historical Ernesto Guevara is irrelevant. Che has become an idea. Or an ideal” (Casey, 125). The “ultimate standard-bearer of revolutionary virtue” (Casey, 101) has been commodified.

It is shameless commercial exploitation, a “breach of the integrity of Che” (Casey, 199). The image of the historical Ernesto, the embodiment of selflessness and self-sacrifice for the cause of socialism, had come to represent booze, sex, and self-gratification. The artistic properties of the image seem to conspire to invite use and abuse: “The shot contains aesthetic magnets — hair, beard, star, beret: reference points for derivative art, facilitating the image’s mass reproduction as a two-tone icon and a plethora of abstract interpretations” (41). Che’s long hair endeared him to sixties youth, but it was hardly a fashion statement. He was merely one of the barbudos (bearded ones) who had been living the guerrilla life in the rural Sierra Maestra mountains of Cuba.

Born in Rosario, Argentina, Che had been one of 82 rebels to join the Cuban revolution in 1956, unique among revolutionaries in joining uprisings “away from their mother countries” (Sharma and Sharma, 4). His radicalization had taken root when, as a young man, he traveled throughout South America on a Norton 500 motorcycle and saw widespread exploitation such as “a beleaguered Chilean worker who had been jailed for being a communist” (2). He also took note of the CIA-backed coup in Guatemala in response to the land reform policies of Jacobo Arbenz, concluding that, “in the face of . . . American imperialism and its cronies, only revolutionary violence could bring liberation” (3).

The idea of “socialism in one country” was anathema to Che (Sharma and Sharma, 5), and he was fiercely determined to expand his revolutionary success in Cuba to guerrilla movements around the world; as he said, “Other nations are calling for the aid of my modest efforts” (quoted in Seddon, 3). In April 1965 Che presented a formal letter to Fidel Castro renouncing his position of Party leadership, his ministry post, his rank of commandante, and his Cuban citizenship. It was a declaration of statelessness and homelessness: “Che belonged nowhere . . . Che belonged everywhere” (Casey, 59).

Cuba was providing aid to national liberation struggles in Africa. Che, in an impassioned speech at the United Nations, denounced Western imperialism and addressed the “tragic case of the Congo” (Seddon, 2). In April 1965 he helped establish an anti-imperialist insurgency in Kigoma, Congo. He reflected on its failure: “I have emerged believing more than ever in guerrilla warfare; but we failed. . . . I will not forget this defeat or its valuable lessons” (Casey, 325). Before leaving the Congo he wrote his parents and critiqued himself as soldier and doctor: “The second doesn’t interest me any longer. As a soldier I am not so bad.” He added, “My Marxism has taken root and become pure,” and signed off as their “prodigal son, Ernesto” (Harris, 49). In 1966 he met with the Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO) in Dar es Salaam and offered to enlist in their revolutionary project. FRELIMO declined his participation. Then, in November 1966, he entered Bolivia to create “a continent-wide communist revolution, with Bolivia at its center” (Rodriguez, 1). Critics though, regarded his action as “an elaborate suicide in the hope of being martyred” (6).

Che and his compañeros were in Bolivia only a short time, plagued by dense jungles, raging rivers, vegetation poor in nutrients, terrain not suited for sustaining mobile combatants, and tormented by biting insects so that “Guevara appeared sick and exhausted” (Castaneda, 397). But there were successes: at Nancahuazu and Iripiti they ambushed and killed 18 government soldiers while suffering no casualties. And on April 10, 1967, they killed nine, wounded a dozen, took thirteen prisoners, and seized needed supplies: “This was the most inspiring episode of the war for the guerrillas; it demoralized the government and encouraged rebel supporters” (366). The humanitarian Dr. Guevara even took time for dentistry in several villages they passed through, performing extractions for suffering villagers. But tragically for the rebels, they were not an organic insurgency: not a single peasant joined their ranks. Even worse, local peasants, pacified by government reforms, served as informants for the government.

A potato farmer observed by moonlight “a band of bearded, emaciated ghosts carrying guns and rucksacks and doubled over under their weight” (Castaneda, 398). He notified the Bolivian army, and in October 1967 Che was captured at Yuro Ravine, force-marched two kilometers to the village of La Higuera, and held prisoner in a schoolhouse until his execution: “Soldiers drew lots and it fell to Lieutenant Mario Teran to finish off the disheveled, limp, depressed, but still defiant man lying on the floor of the school at La Higuera” (401). The presence of CIA agent Felix Rodriguez, hero to the gusanos (Cuban exiles) of Miami, means that Che truly died fighting yanqui imperialism. And U.S. Rangers were at Yuro Ravine, “responsible for capturing Che and almost completely eliminating his small force” (Harris, 220). Even U.S. President Johnson had been monitoring Che’s efforts in Bolivia. Rodriguez later wrote of Che, “His moment of truth had come, and he was conducting himself like a man . . . facing death with courage and grace” (Casey, 238).

Then, “unwittingly, the Bolivian military delivered the world . . . a crucified Che” (Casey, 186). Bolivian photographer Freddy Alborta had snapped a photo of Che in death, aged 39, half-naked, his body laid across a wash trough in a grungy laundry room. It is the supine Che with “a Christlike serenity,” who “looked strikingly alive, lying in a state of tranquility and repose” (48, 179). Che found “the destiny he sought” (183), since, from early youth, “he had yearned for a Christlike destiny, an exemplary sacrifice” (Castaneda, 352). It is even said that “he had to go beyond matter” (Casey, 297), a comment seemingly rooted in Karl Marx’s observation of “spirit” being “burdened with matter” (Germany Ideology).

Then, “unwittingly, the Bolivian military delivered the world . . . a crucified Che” (Casey, 186). Bolivian photographer Freddy Alborta had snapped a photo of Che in death, aged 39, half-naked, his body laid across a wash trough in a grungy laundry room. It is the supine Che with “a Christlike serenity,” who “looked strikingly alive, lying in a state of tranquility and repose” (48, 179). Che found “the destiny he sought” (183), since, from early youth, “he had yearned for a Christlike destiny, an exemplary sacrifice” (Castaneda, 352). It is even said that “he had to go beyond matter” (Casey, 297), a comment seemingly rooted in Karl Marx’s observation of “spirit” being “burdened with matter” (Germany Ideology).

This photo is Che “exuding the wisdom of the dead” (Casey, 181). As with the Korda Che, Che’s eyes are compelling: “Those easily recognizable eyes — were wide open and, it seemed, at peace. There was no fear in those eyes. He looks at us with neither condemnation nor pity . . . looking at his tormentors and pardoning them because they know not what they are doing, and looking at the world, assuring it that one does not suffer when one dies for one’s ideas” (181). Art historians and scholars say the image is derivative of a great painting, Andrea Mantegna’s Lamentation over the Dead Christ. Ironically, Che had written, “I am the very opposite of Christ. . . . I will fight with all the arms within reach, instead of letting myself be nailed to a cross” (61). In his 1967 article in Tricontinental magazine in which he called for “the creation of two, three, several Vietnams,” Che also urged “hatred as an element of struggle; unbending hatred for the enemy, which pushes a human being beyond his natural limitations, making him into an effective, violent, selective, and cold-blooded killing machine . . . a people without hatred cannot triumph over a brutal enemy” (in Casey, 370).

Che’s first death was “at La Higuera, in the wilds of the Bolivian southeast, on a morning in October” (Castaneda, 390). His second death is in capitalism’s commodification of his image. Marx saw that capitalism is predatory and voracious, unleashing “the most violent, mean, and malignant passions of the human breast, the furies of private interest” so that every object, person, and creature is “transformed into property” (Capital). Even Commandante Guevara, who declared that a true revolutionary is “guided by a great feeling of love” (Casey, 62), has now been officially reduced, via the Korda Che, to private property and designated a nine-character alphanumeric code: U.S. GATT visual art copyright number VA-1-276-975.

Against this commodification is “the most complete human being of our age,” as Jean-Paul Sartre described him (quoted in Sharma and Sharma, 5): humanist, Marxist revolutionary, medical doctor, combat soldier, government minister, writer, husband, father, UN orator, and iconic leader. Che was also the “New Man” of the socialist society he envisioned. His Marxist, revolutionary spirit defies commodification. In a last letter to his children, he wrote, “Above all, always be capable of feeling deeply any injustice committed against anyone, anywhere in the world. This is the most beautiful quality in a revolutionary” (Seddon, 9). He urged us all to “tremble with indignation at any injustice” (Casey, 168).

El Che Vive!

Sources

Anatomy Films, “Replication Infinitum,” 2021.

Michael Casey, Che’s Afterlife: The Legacy of an Image (New York: Vintage Books, 2009).

Jorge G. Castaneda, Companero (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1997).

Richard L. Harris, Death of a Revolutionary (New York: W.W. Norton, 2000).

Christopher Rodriguez, “The Bolivian Insurgency of 1966–1967: Che Guevara’s Final Failure,” Small Wars Journal, September 23, 2018.

David Seddon, “Che Guevara in the Congo,” Jacobin, April 4, 2017.

Shubham Sharma and Rishav Sharma, “Remembering Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara on his 93rd Birth Anniversary,” Monthly Review Online, June 16, 2021.

Images: Photo by Albert Korda (Wikipedia, public domain); Iconic reproduction of Korda’s photo, Anatomy Films (public domain); Korda’s film roll containing his famous photo of Che (Wikipedia, public domain); photo by Freddy Alborta (Wikipedia, fair use).

Join Now

Join Now