March is Women’s History Month and U.S. social media is filled with exaltations of corporate women breaking the glass ceiling; celebrations of women in the imperialist military and police forces; and blowout sales on women’s clothing, cosmetics, and home decor. Less popularized are the watershed moments led by working class women, the commemorations of women’s rights revolutionaries, as well as the current crises that women face, much less what to do about it.

But Women’s History Month is centered around March 8 — International Women’s Day, a holiday rooted in socialist politics. March 8 has long been celebrated throughout the world, and yet, until recently, it has been virtually forgotten in the U.S., where initial struggles leading to its establishment took place.

IWD History

While historians and activists alike continue to debate the chronology of events, we know that 15,000 women needle trades workers in New York City marched in 1908 under the slogans, “For an Eight Hour Day,” “For the End of Child Labor,” and “Equal Suffrage for Women.” Two months later, Socialist Party women began organizing a first mass rally for the following February in New York City, where thousands gathered to hear speeches by socialists and women trade union leaders like Leonara O’Reilly. The following year, Rose Schneiderman, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, and Metta Stern addressed celebrants at Carnegie Hall.

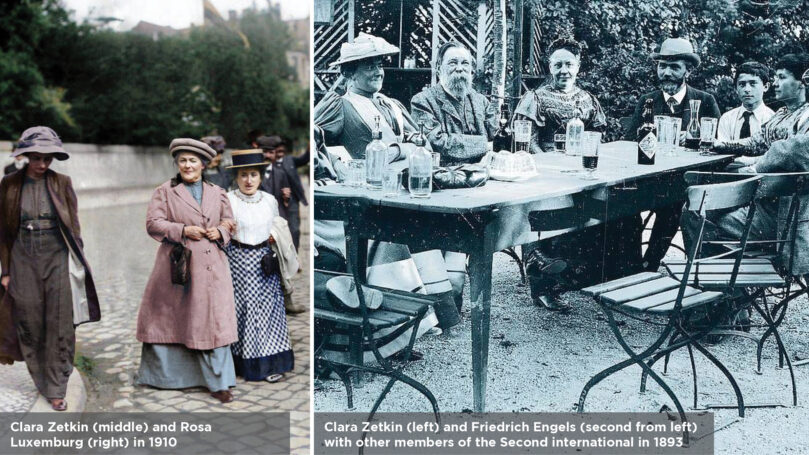

However, we also know that the revolutionary Clara Zetkin had a lot to do with the establishment of the holiday. Some state the 1907 Socialist women’s conference, under her leadership, held during the Congress of the Second International, influenced U.S. Socialists to recognize the day a year later. Others state Socialist Party members in the U.S. prompted Zetkin to push for the holiday at a world-wide level, when the Second International met again in 1910. In any case, it was at the International’s 1910 Congress that the Socialist movement formally adopted International Women’s Day.

Working class women were among the many Communards who fought in battle and pushed for such rights as equal pay and access to education.

Initially, they set the date for March 18, to commemorate the 40th anniversary of the 1871 Paris Commune. Here, revolutionary working class women were among the many insurrectionary leaders, who fought to establish a revolutionary government in the aftermath of the Franco-Prussian War. The Communards, as they were known — including Louise Michel, Elisabeth Dmitrieff, Nathalie Lemel, Léontine Suétens and so many others — fought in battle and pushed for such rights as equal pay and access to education. Much of Eleanor Marx’ later organizing, among women workers in London, for example, was inspired by these revolutionary women. Her popular writings on the Commune’s history reflected the refugee community that had settled in London, in the wake of the Communards’ defeat and repression.

By 1913, all parties concerned agreed on an annual date of March 8. As World War I dragged on, the holiday became a way to mobilize against the war in a number of countries. Most dramatically, working women in Petrograd, Russia mobilized in political strikes against the war on March 8, 1917. They demanded bread and peace: an end to the war and food shortages, the return of their husbands and sons from the war front, and an end to czarist rule.1 Their protests sparked the Revolution. By 1922, the Soviet Union led the institutionalization of March 8 as a formal holiday. It was readily recognized by other socialist countries, and remains a holiday even in many countries where socialism was later overthrown.

Women’s rights today

March 8 is still celebrated and commemorated around the world, perhaps more so now than ever. And women everywhere are increasingly utilizing the holiday as a day of action. Women’s rights are sliding backwards, as country after country seems to move further and further to the right. Most dramatically, women in Afghanistan — in a single lifetime — went from full voting rights and a rich public and work life, with access to education and health care, to a world of almost total sequestering and isolation, stripped of the most basic rights of survival. The terrifying reversal in that country began with U.S. military support for anti-Communist guerrillas in 1979, setting off a process of destabilization and reaction that was only deepened by the U.S.’ 2001 invasion. Afghanistan was ranked last in the 2023 Global Index on Women’s Status. The U.S. itself, though, ranked only 37th in 2023. And with Trump, Musk & Co.’s Project 2025 slash and burn agenda, it is sure to get much lower.

Women of color are even more super-exploited as workers.

There is the generalized feminization of poverty. In the U.S., women make up 60% of minimum wage workers. And while numbers vary, women overall are paid just 78 cents for every dollar that men are paid. Women of color are even more super-exploited as workers. Black women are paid 66 cents, Latinas — who comprise the largest number of undocumented women workers — just 57 cents, and Native women workers are paid close to half of what men overall are paid: 52 cents on the dollar.

On union jobs, women make the same. That’s huge for women in a country that dropped from 27th to 43rd in gender equity in just one year, according to the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report for 2023.

On union jobs, women make the same. That’s huge for women in a country that dropped from 27th to 43rd in gender equity in just one year, according to the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Report for 2023.

Increased restrictions on women’s reproductive rights have been front and center for women’s actions in the U.S. with the recent overturning of Roe v. Wade. Twelve states have outright bans, while all but nine plus D.C. have some form of increased restrictions. This has spilled over into denial of pre and postnatal care, which has become a life and death issue for women across the country, as well as restricted access to birth control methods. At least four states have proposed the death penalty for those who do access abortion. Having control over the timing and size of one’s future family, or whether to even have a family, can largely dictate one’s ability to work, go to school, or participate substantively in public life.

But it hasn’t stopped there. The removal of “DEI” protections can only work to further prevent women from gaining equal access to public health resources, higher education, and the workforce, while making them more easily discriminated against in hiring and retention. The further defunding of public education, increase in school “choice” vouchers, and promotion of home schooling will only further drive women back into the domestic isolation of the home.

So far, the pushback has come in the form of mass demonstrations, town hall protests, lawsuits, and plans for the 2026 midterm elections. But not so long ago, working-class women took matters into their own hands to advance a whole set of demands to secure work and reproductive rights, health care, child care, and legislative reforms, all within the framework of their union and in solidarity with their union brothers.

Union women

The experience of the District 31 USWA Women’s Caucus, in the 1970s Calumet Steel region of Southeast Chicago and Northwest Indiana, provides many lessons for labor and social justice activists today. It drew attention to: gender and reproductive health discrimination, discouragement and obstacles in job retention and access to skilled apprenticeships, race discrimination and probationary firings, poor training and occupational segregation, the need for childcare and adequate locker rooms on the job, and broader legislative activity like the struggle for the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment and the Pregnancy Discrimination Act. These are all issues which we are still dealing with today.

The Women’s Caucus argued that reproductive hazards affected both men and women, calling for an altering of the workplace, rather than the workforce.

One of the main issues the Women’s Caucus organized and unified around was pregnancy discrimination. Many industries turned new occupational safety and health language on its head to justify purging women of childbearing age from high paying union jobs, out of supposed concern for their future children. The Women’s Caucus argued that reproductive hazards affected both men and women. They appealed to male coworkers by insisting that to exclude women from a toxic worksite only served to leave men exposed and called for an altering of the workplace, rather than the workforce. USWA women made common cause with their male coworkers by placing the burden on management to clean up the workplace, rather than reinforce dangerous illusions that health hazards would somehow vanish if only women were driven from industry.

With the renewed attacks on the most basic democratic rights for women, we can learn a lot from the lesser known militants, like steel worker women, who found a way to use the social power of their unions to champion reproductive health and workers’ rights more broadly.

Happy International Women’s Day!

1. The demand for bread and peace would eventually, under Lenin’s leadership, grow into the general slogan, “Bread, Peace, and Land,” uniting the working-class and peasantry in the struggle for a new society. The February Revolution was sparked by women textile workers striking. Their main demands were ‘down with the autocracy’ and an end to the war. As the strike grew to hundreds of thousands, a largely peasant-based army was sent in to crush the uprising. At this point, striking workers fraternized with troops, appealed to them as soldiers and sailors, and demanded, “drop your weapons and join us.” And most did. While historians often claim this was a spontaneous uprising, the Bolsheviks made the point that their years of influence in clandestine worker circles helped shape the consciousness of these workers to carefully gauge and act accordingly, in their absence. By February 1917, much of the Bolshevik leadership was either in exile, in police custody, or simply too weakened by wartime state repression to provide the required leadership. It was only in the aftermath, when Lenin returned in April and when it was clear the liberals were attempting to put a break on revolutionary activity, that Lenin introduced the slogan, “Bread, Peace, and Land.” The slogan immediately resonated and spread like wildfire.↩

The opinions of the author do not necessarily reflect the positions of the CPUSA.

Images: The Chesapeake Bay CLUW Chapter proudly presents its 2nd Spring Fashion Show: “Union Women In Uniform” by CLUW National (X); Clara Zetkin with Rosa Luxemburg colorized (Pour comprendre avec Rosa Luxemburg) / Zetkin with Engels (public domain); USWA District 31 march

Join Now

Join Now